|

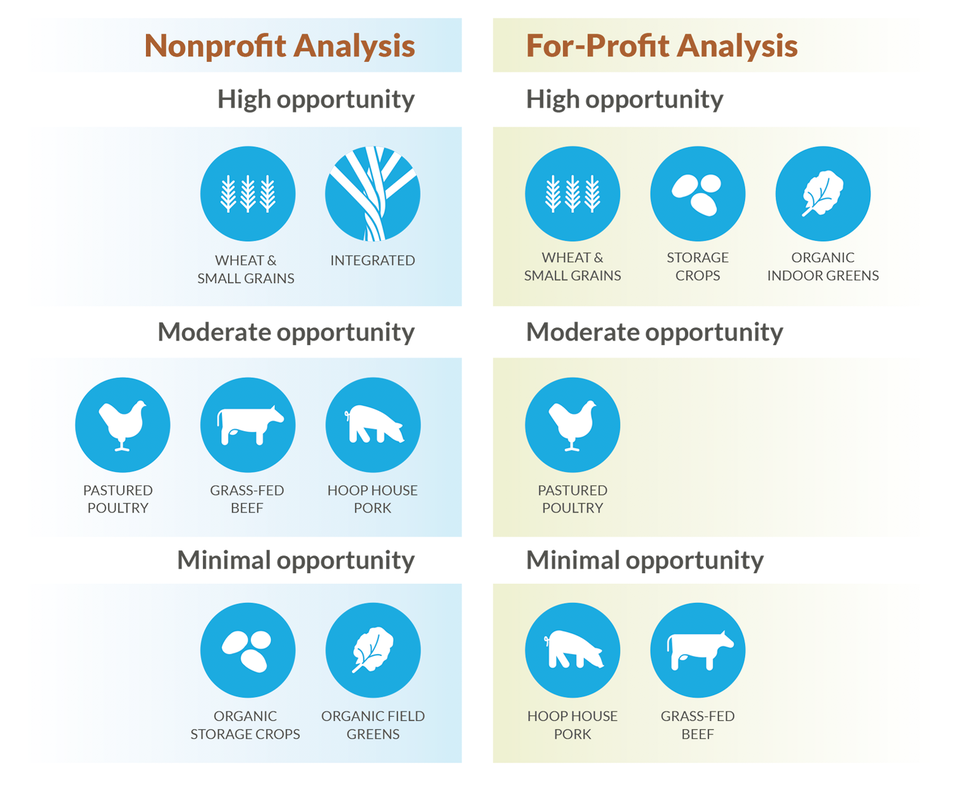

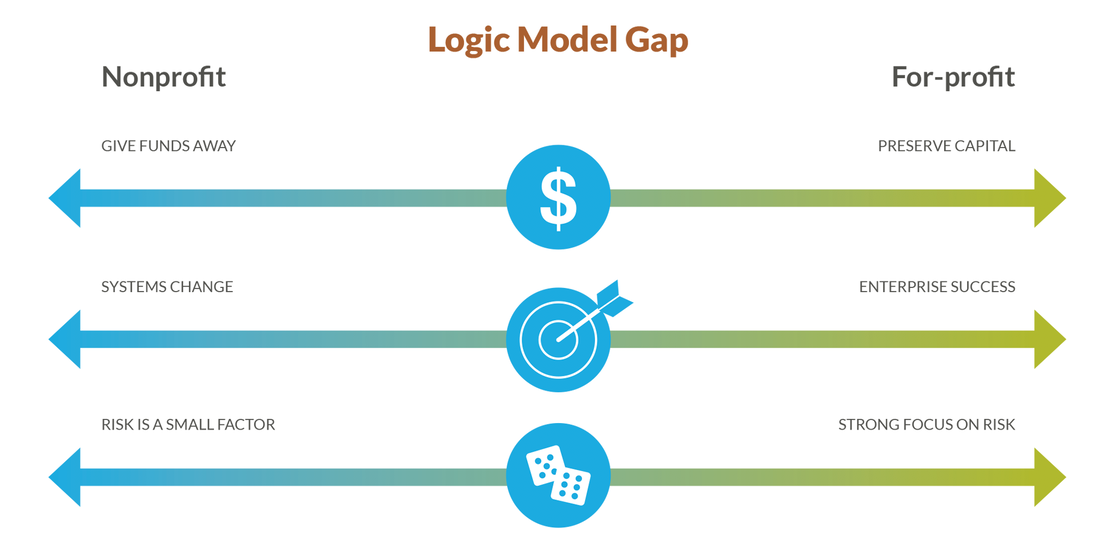

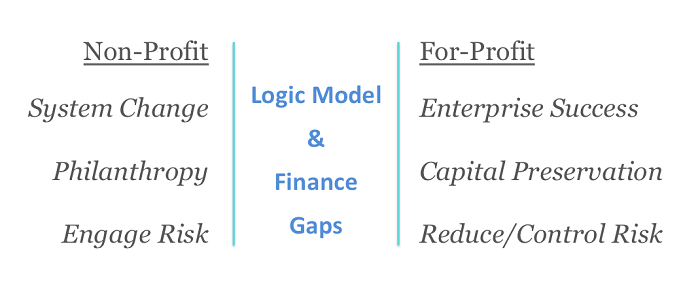

What happens when philanthropy meets the profit motive in sustainable food investing? This is a short summary of what CFFP uncovered when traditional investors joined philanthropists to invest in sustainable food systems. Our group includes foundations and impact investors in the U.S. states of Washington and Oregon. We all came to the table in support of “investment” as a tool to create sustainable food systems. But it took a few years to find a common vision for the investing work. What took so long? We think it is because our philanthropists and traditional investors have very different experiences with money, risk and achieving success. These experiences create what we call for-profit and non-profit “logic models” that can shape widely divergent expectations of the investing activity. CFFP found a path forward on investing that reconciled our for- and non-profit mindsets. We offer our thinking on the logic gap to help other collaborative groups move forward toward investing in sustainable food systems. In early 2016 CFFP hired Ecotrust, a high-functioning regional non-profit, to research market factors in six food sectors: beef, poultry, pork, small grains, leafy greens and storage crops. The goal was to identify sustainable production models already in use, identify the market drivers and investment opportunities, inform outreach to potential financiers, and determine whether a dedicated fund should be established in Washington and Oregon. CFFP hoped to align different types of capital around the findings of the Ecotrust report. The full market research successfully identified sustainable production models currently in use along with specific supply and demand drivers for each product. However, when presented with the same information, non-profit and for-profit investors had different conclusions on how the collaborative should proceed. Ecotrust had made its recommendations as a non-profit investor. It focused on opportunities that could transform the actual system of food and agriculture, especially those working on overarching sustainability goals and crossing product lines. For example, no-till grains can generate grain and improve soil health and sequester carbon and be used for chicken feed. In contrast, Mark Bowman, a seasoned agricultural lender, analyzed the same data as a for-profit investor. He emphasized investment repayment factors: production costs, potential linkages and gaps for investors, industry trends, business configuration and entrepreneur expertise. Surprised, CFFP partners discussed the divergent recommendations and what they meant for the group’s next steps. Foundations tend to fund for transformational system change, they observed, while for-profit investors seek to “pick winners” based on transactional financial success. In other words, non-profit audiences reading the report sought opportunities to transform the overall food system, while for-profit investors looked for enterprises with the best chance of repaying their investments.

“It was described as a difference between a utopian ‘I want to change the world’ view to a ‘what’s actually going to provide some returns?’ view,” said Mauri Ingram, Whatcom Community Foundation CEO, who praised Tim Crosby, Project Coordinator, for having the research evaluated from both points of view. The logic model gap between non-profit and for-profit investors needs to be acknowledged and overcome, CFFP members agreed, for any project seeking to bring funders together for maximum community benefit — not only for investing in a regional food system, but for any issue area, in any geographic footprint.

0 Comments

Philanthropy Northwest, our fiscal sponsor, generated a case study about CFFP highlighting the road we have been traveling as well as innovative research we have generated.

From cultural giving traditions to tech boom wealth creation, philanthropy in the Pacific Northwest has forged a reputation for blending collaboration and innovation. In this spirit, the Cascadia Foodshed Financing Project (CFFP) aims to bring foundations and individual impact investors together to improve the regional food economy. This case study of the project identifies untapped areas for co-investment in Oregon and Washington, then outlines a combination of grantmaking and investment strategies for transformational impact. Get Case Study here... Harvesting Opportunity: The Power of Regional Food System Investment to Transform Communities8/23/2017 This month, the Federal Reserve Bank launched a report entitled Harvesting Opportunity: The Power of Regional Food System Investment to Transform Communities. This publication is a curated collection of research, reports, and essays written by community development experts that explore the potential for local and regional food system investment to change local economies, with the explicit end goal of improving equity for low and middle income households and communities. The essays provide insight from a variety of perspectives including finance, government, academia, philanthropy, and more.

Overarching takeaways include the imperative of cross sector collaboration, and the necessity for a wide variety of capital to meet diverse needs of local and regional food systems at differing levels of production. This and other key lessons from the report confirm CFFP endeavors to build knowledge including the Ecotrust Regional Food Market Research, accompanying lender analysis, and exploration of a relationship with the CDFI Craft3. CFFP Coordinator Tim Crosby spoke this month at the launch of the report in Washington DC. In tandem with its release, CFFP has prepared a high-level synopsis with bulleted takeaways from each chapter as an entry point to the full publication. Read the synopsis below, and find the full report online here. Impact Measurement: How much is too much? How much is not enough?

Devin Thorpe, Forbes As CFFP emerges from it’s research phase and begins to collaborate with Craft3 in the more tangible work of making and tracking investments, it’s important to ask several questions. These questions stem from our ever-present quandary of “how good is good enough?” and sound something like “what is our standard for impact?” “how will we track progress?” and “how will we tell our story?”. Impact measurement, management, and evaluation lend a wealth of tools to address these questions. This article, last in a three-part series on impact measurement, presents perspectives from impact investment experts from around the globe on their experiences surrounding impact measurement and its added value in impact investing work. While recommendations vary widely, a few common themes emerged:

Lastly, the author and interviewees emphasize that while impact measurement and management often sounds daunting to investors who are unfamiliar with tracking anything beyond financial outcomes, reporting is important. Collection of impact data contributes the evidence base for impact investing as a financial tool and catalyst of change. Contributing to this evidence base is both a responsibility and community-building privilege in transforming mainstream investment practices. Amazon Meets with Ranchers to Expand Organic Meat Distribution

Fortune According to the Organic Trade Association, U.S. sales of organic meat and poultry increased by 17% last year, it’s fastest annual growth ever. This shows huge promise for the product categories that CFFP illuminated as investible opportunities in the PNW. Although the Ecotrust Market Research did not investigate organic meat production explicitly, producers contacted through the research such as Botany Bay Farms often incorporated organic practices into poultry and pork production by default of their farming philosophies. In other words, organic (both certified and uncertified) comes with the territory of alternative meat production systems for some producers in the PNW. Through its acquisition of Whole Foods, logistical experts like Amazon may meet key infrastructural gaps for local meat producers. After its purchase of Whole Foods in mid June of this year, Amazon is planning to meet with a group of US ranchers seeking to expand distribution of organic and grass-fed meats. Participating ranchers include Will Harris of White Oak Pastures in Georgia, who is excited about the increased efficiency that Amazon is able to bring to processing, packaging, and distribution of his organic and grass-fed products. Other farmers are apprehensive about Amazon pivoting to source from abroad to lower costs of organic and grass-fed beef. Mark Smith of Aspen Island Ranch, who currently sells to Whole Foods through a cooperative, sums it up: “It could be as bad a shutting us out or as good as expanding our markets”. The demand for local food is growing - here's why investors should pay attention | Summary8/23/2017 The demand for local food is growing – here’s why investors should pay attention.

Oran B Hesterman, PhD and Daniel Horan, Business Insider As local investors in the food space, we at CFFP experience the hard work of food production, infrastructure, funding, and financing. We see local farm operations struggling or closing, and we see the community-level effects of net decreases in farm income. It’s easy to feel isolated in our mission to build the PNW regional food system. However, this article presents solid evidence for an increase in consumer demand, especially within the last 2-3 years that CFFP has been incubating, that gives momentum to our mission. As this article brings to the mainstream a statement that CFFP members have felt to be self-evident: “Investors that deploy patient capital in successful food and farming enterprises are in a position not only to garner financial returns but also to create value for other stakeholders, making positive social impact supporting healthy communities, strong local economies, and environmental resilience” Demand for local food is growing. In 2016, there was a 20% increase in food and beverage deals made by venture capital funds according to Dow Jones VentureSource, and the list of food-focused accelerators and incubators continues to grow. Local food sales grew from $5 billion to $12 billion between 2008 and 2014, and sales are predicted to jump to $20 billion by 2019. The number of farmers markets in the nation has increased by 380% in the last two decades. As this article points out, however, “it’s not as simple as it should be” mainly due to issues of scale and infrastructure for small and midsize farms. Still, growing attention and momentum from investors presents potential for an influx in capital leverage to address these challenges. No, poor people don’t eat the most fast food

Jay L. Zagorsky and Patricia Smith, CNN This study breaks down stereotypes about low-income consumption habits and illuminates causes behind fast food consumption that may lead to more effective solutions. For instance, the study found that those who read ingredients on their food are less likely to eat fast food. Those who work higher hours are more likely to eat fast food. Increased availability and convenience of healthy foods emerges as a lynchpin for reducing consumption of fast foods and consequential health impacts. CFFPs partnership with Craft3 has opened avenues to invest in exactly those types of opportunities, such as local healthy food trucks. It is a common perception that a disproportionate number of overweight Americans are low-income because low-income groups consume more fast food, being that it’s “cheaper” than healthy food. This has resulted in policies regulating access to fast food in low-income communities, educational campaigns targeting schools in low-income communities about behavioral changes towards healthier eating habits, and more. However, a recent study by the authors reveals that “we’re all loving it”: 73.6% of top earners stated they had eaten fast food in the last seven days, and 85% of middle-income respondents stated the same. Surprisingly, about 80.6% of the poorest respondents reported eating fast food in the last week. While a high percentage Americans reported consuming fast food, middle-income consumers – not low-income consumers – were the largest demographic. As Cascadia Foodshed Financing Project works at the intersection of food, finance, and philanthropy to transform the Pacific Northwest regional food system, we ask the question, “how good is good enough?” with regards to individual investment opportunities. Does the investment meet a need expressed by the community? What ripple effects might the investment have? Social impact advisor Katherine Pease of KP Advisors asks this critical question of the impact investing field at large. In a recent report, In Pursuit of Deeper Impact, Pease challenges the status quo of impact investing as “conventional impact investment practices often fail to incorporate an analysis of the root causes of inequality”. As a result, impact investing works often as a series of isolated transactions that yield measurable positive social and environmental outputs, but fail to contribute to the transformation of deep and systemic causes of inequity. This is a tension that resonates with the logic and model gap between investment for enterprise success and systems change that CFFP uncovered through market research analysis with Ecotrust in 2016: So what can we do, as impact investors who are serious about laboring towards deep and lasting transformation in our food system?

"Evidence-based", "systems change", "enterprise success" -- what do we really mean when we use these words? Learn more about CFFP's approach to impact in our latest article at the Philanthropy Northwest blog: "Ground Truth: Between Nonprofit & For-Profit Paths for Impact"

Will 2017 be the year we get serious about sustainable food?

Ucilia Wang, The Guardian This article covers the status of several trends towards food sustainability in the United States including organic conversion, eliminating antibiotic use, regulation of illegal fishing, and reducing meat consumption. Each area contains its own successes and challenges, but with an equal sense of urgency: John Reganold, soil science professor at WSU, states, “In a time of increasing population growth, climate change, and environmental degradation, we need agricultural systems that come with a more balanced portfolio of sustainability benefits” Towards which of these four sustainability trends can CFFP contribute? How can we use our financial resources to leverage that “balanced portfolio of sustainability benefits” in our food system? Can we serve as a security buffer that eases local producer transitions to organic? Can we invest in antibiotic-free meat producers and sustainable seafood suppliers? Can we support consumer education and broaden skillsets around alternative proteins? |

LearnAs part of its own research, CFFP regularly illuminates educative research, media, and resources related to our work. This page contains public versions of our synopses. Archives

June 2019

Categories

All

|

© Cascadia Foodshed Financing Project 2016

1521 10th Pl N, Edmonds, WA 98020 | (206) 300-9860 | [email protected]

1521 10th Pl N, Edmonds, WA 98020 | (206) 300-9860 | [email protected]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed